Santa Claus is one of the most remarkable figure associated with Christmas. Santa has always been an essential part of the Christmas celebration, but the modern image of Santa didn't develop until well into the 19th century. Moreover, he didn't spring to life fully-formed as a literary creation or a commercial invention. Santa Claus was an evolutionary creation, brought about by the fusion of two christian religious personages (St. Nicholas and Christkindlein, the Christ child).

In 1804, New York Historical Society was founded with Nicholas as its patron saint, its members reviving the Dutch tradition of St. Nicholas as a gift-bringer. In 1809, Washington Irving published his satirical A History of New York, by one "Diedrich Knickerbocker," a work that poked fun at New York's Dutch past (St. Nicholas included).

When Irving became a member of the Society the following year, the annual St. Nicholas Day dinner festivities included a woodcut of the traditional Nicholas figure (tall, with long robes) accompanied by a Dutch rhyme about "Sancte Claus" (in Dutch, "Sinterklaas"). Irving revised his History of New York in 1812, adding details about Nicholas' "riding over the tops of the trees, in that selfsame waggon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children." In 1821, a New York printer named William Gilley issued a poem about a "Santeclaus" who dressed all in fur and drove a sleigh pulled by one reindeer.

On Christmas Eve of 1822, another New Yorker, Clement Clarke Moore, wrote down and read to his children a series of verses; his poem was published a year later as "An Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas" Moore gave St. Nick eight reindeers (and named them all), and he devised the now-familiar entrance by chimney.

Meanwhile, in parts of Europe such as Germany, Nicholas the gift-giver had been superseded by a representation of the infant Jesus (the Christ child, or "Christkindlein"). The Christkindlein accompanied Nicholas-like figures with other names (such as "Père N?el" in France), or he travelled with a dwarf-like helper (known in some places as "Pelznickel," or Nicholas with furs). Belsnickle (as Pelznickel was known in the German-American dialect of Pennsylvania) was represented by adults who dressed in furry disguises (including false whiskers), visited while children were still awake, and put on a scary performance. Gifts found by children the next morning were credited to Christkindlein, who had come while everyone was asleep. Over time, the non-visible Christkindlein (whose name mutated into "Kriss Kringle") was overshadowed by the visible Belsnickle, and both of them became confused with St. Nicholas and the emerging figure of Santa Claus.

The Louis Prang 1886 Christmas card modern Santa Claus derived from these two images: St. Nicholas the elf-like gift bringer described by Moore, and a friendlier "Kriss Kringle" amalgam of the Christkindlein and Pelznickel figures. The man-sized version of Santa became the dominant image around 1841, when a Philadelphia merchant named J.W. Parkinson hired a man to dress in "Criscringle" clothing and climb the chimney outside his shop.

In 1863, a caricaturist for Harper's Weekly named Thomas Nast began developing his own image of Santa. Nast gave his figure a "flowing set of whiskers" and dressed him "all in fur, from his head to his foot." Nast's 1866 montage entitled "Santa Claus and His Works" established Santa as a maker of toys; an 1869 book of the same name collected new Nast drawings with a poem by George P. Haddon Sundblom illustration Webster that identified the North Pole as Santa's home.

The Santa Claus figure, although not yet standardized, was ubiquitous by the late 19th century. Santa was portrayed as both large and small; he was usually round but sometimes of normal or slight build; and he dressed in furs (like Belsnickle) or cloth suits of red, blue, green, or purple. A Boston printer named Louis Prang introduced the English custom of Christmas cards to America, and in 1885 he issued a card featuring a red-suited Santa. The chubby Santa with a red suit (like an "overweight superhero") began to replace the fur-dressed Belsnickle image and the multicolored Santas.

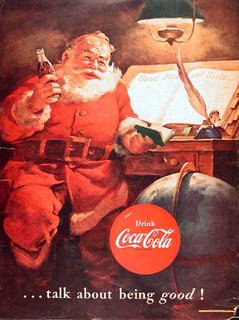

At the beginning of the 1930s, the burgeoning Coca-Cola company was still looking for ways to increase sales of their product during winter, then a slow time of year for the soft drink market. They turned to a talented commercial illustrator named Haddon Sundblom, who created a series of memorable drawings that associated the figure of a larger than life, red-and-white garbed Santa Claus with Coca-Cola. Coke's annual advertisements — featuring Sundblom-drawn Santas holding bottles of Coca-Cola, drinking Coca-Cola, receiving Coca-Cola as gifts, and especially enjoying Coca-Cola — became a perennial Christmastime feature which helped spur Coca-Cola sales throughout the winter (and produced the bonus effect of appealing quite strongly to children, an important segment of the soft drink market). The success of this advertising campaign has helped fuel the legend that Coca-Cola actually invented the image of the modern Santa Claus, decking him out in a red-and-white suit to promote the company colors — or that at the very least, Coca-Cola chose to promote the red-and-white version of Santa Claus over a variety of competing Santa figures in order to establish it as the accepted

image of Santa Claus.

So complete was the colonization of Christmas that Coke's Santa had elbowed aside all comers by the 1940s. He was the Santa of the 1947 movie Miracle on 34th Street just as he is the Santa of the recent film The Santa Clause. He is the Santa on Hallmark cards, he is the Santa riding the Norelco shaver each Christmas season, he is the department-store Santa, and he is even the Salvation Army Santa!

Long live Santa Claus!!!!!!!!!!!!

No comments:

Post a Comment